About

Southern Resident orca, J40, shows CWR researchers her teeth and tongue during Encounter #28 on May 26, 2022.

About ORCAS: Landing Points

NAMING // TAXONOMY // ECOTYPES // LIFESPAN & REPRODUCTION

BABY ORCA(S) // APPEARANCE & MORPHOLOGY // BEHAVIORS

SOCIAL STRUCTURE // RANGE // COMMUNICATION // STATUS & THREATS

All photographs and information on whalesearch.com are Copyright © 2024 Center for Whale Research.

The killer whale or orca (Orcinus orca) is a toothed whale, the largest member of the dolphin family, and an apex predator in the world’s oceans. Three orca ecotypes inhabit Pacific Northwest waters: Resident, Bigg’s (Transient), and Offshore.

NAMING

The common name is killer whale or orca; other names include blackfish, grampus, and killer.

Most English-speaking scientists use killer whale when referring to the species, although orca is increasingly common—amateur followers and the general public use orca solely.

Pacific Northwest First Nations orca names include:

-

Ka-kow-wud (Quillayute, Olympic Peninsula)

-

Klasqo’kapix (Makah, Olympic Peninsula)

-

Qaqawun (Nootka, west-side of Vancouver Island)

-

Max’inux (Kwakiutl, north Vancouver Island)

-

Ska-ana (Haida, Queen Charlotte Islands)

J16 Tail Slap in San Juan Channel on January 27, 2024

Individual whales received an alpha-numeric designation based on the letter of their pod and the identification sequence.

See Southern Resident Orca (SRKW) POPULATION.

TAXONOMY

Taxonomy (Scientific Classification)

Kingdom:

Phylum:

Class:

Order:

Suborder:

Family:

Genus:

Species:

Animalia

Chordata

Mammalia

Cetacea

Odontoceti

Delphinidae

Orcinus

Orca

Orcas are one of thirty-five (35) species in the oceanic dolphin family, Delphinidae.

Orcas are in the suborder Odontoceti or toothed whales—referred to as Odontocetes.

Odontocetes differ from other cetaceans (whales and dolphins) because they have teeth instead of baleen (like humpbacks and grey whales).

Orcas are the largest species of oceanic dolphin. Oceanic dolphins are the most diverse group of toothed whales (suborder Odontoceti), with 35 species.

Other similar species include Pygmy killer whales, False killer whales, and Pilot whales.

Click chart to enlarge

Orcas are the most cosmopolitan of all marine mammals and inhabit all of the world’s oceans.

Fish-eating Southern Residents, K12s, (above) sharing their favored prey: Chinook salmon.

Marine mammal-eating Bigg’s, T41A2, eyes its next meal, a Stellar sea lion, during 2024 OS Encounter #14.

ECOTYPES

Research in the Pacific Northwest has identified three orca ecotypes inhabiting the west coast of the United States and Canada.

Resident:

-

Southern Resident (SRKW) designated as J, K, and L pods; currently 73 in this population

-

Northern Resident (NRKW) comprised of A, G, and R clans; 34 matrilines; NRKW population over 300

Fisheries and Oceans Canada NRKW Photo-ID Catalogue and Status Report (2019)

-

Genetically distinct

-

Dorsal fin has a rounded tip, but usually with a sharper angle at the rear corner

-

Open saddle patches are common, with significant variations in shape

-

Historically travel in large family groups

-

Very vocal and socially active

-

J pod is the most frequently seen of the Southern Residents

-

Do not mix socially with Bigg’s (Transient)

-

Evidence of inhabitation for 120,000-140,000 years.

Bigg’s (Transient):

-

Population comprised of an estimated 350 individuals; some families seen more frequently than others

-

Individuals range from Southern Alaska to Oregon and perhaps Northern California

-

More fluid family structure than Residents

-

Pointy, shark-like dorsal fin; saddle patch large and uniformly grey (no open saddles documented in Bigg’s)

-

Travel in small groups

-

Eat marine mammals like seals, sea lions, porpoises, and even other whales

-

Keep a low profile when hunting

-

Do not mix socially with Residents

-

Evidence of inhabitation goes back 300,000 years.

Offshore:

-

Little is known about this ecotype and its habits; discovered in 1988

-

Genetically distinct from Resident and Bigg’s; appear to be smaller, females characterized by continuously rounded dorsal fin tip (usually lack the sharper angle at the rear corner)

-

Saddle patch is usually solid (occasionally open)

-

Travel far from shore between the Aleutian Islands and Southern California

-

mostly seen off the west coast of Vancouver Island and near Haida Gwaii

-

Typically congregate in groups of 20–75 animals (occasional large groups up to 200)

-

Diet likely consists of sharks and other long-lived fish species.

Where else on Earth are orcas seen?

Killer whales (orca) are the most cosmopolitan of all marine mammals. There are at least ten distinct ecotypes (prey specialists and generalists) of orcas. They tend to congregate in certain areas, mostly in cold water:

-

From California to Alaska, the North Pacific is home to some of the largest concentrations of orcas; the inland waters around the San Juan Islands in Washington State and southwestern British Columbia are probably the best locations in the world to view killer whales in the wild.

-

Orcas are most abundant in Antarctica, inhabited by an estimated 25,000-27,000 killer whales, making them the third most abundant cetacean in that area.

-

Known and distinct groups of killer whales are also found in the North Atlantic around Iceland, Norway, and Scotland.

-

The Peninsula Valdez waters of Argentina are home to a population of killer whales well-known for teaching their offspring to partially beach themselves when hunting young Elephant seals.

-

Along the shores of the Crozet Islands, south of Madagascar, a distinct population of orcas has been observed feeding on young sea lions learning to swim.

-

Known populations of killer whales live around New Zealand; they eat a variety of prey, including rays.

The life cycle of killer whales (orca) is similar to that of humans.

Southern Resident orca, J1/RUFFLES, was fifty-nine years old at the time of his death in 2010.

J2/GRANNY was estimated to be 70-90 years old when she died in 2016.

Lifespan

Males:

-

Between twelve and fifteen years old, their dorsal fin begins growing taller and straighter, indicating the onset of sexual maturity

-

Male orcas are sexually mature in terms of physiology, probably in their mid-teens typically; fully physically mature around 25

-

They don’t sire offspring until around age 20; the youngest age of paternity is 15

-

The most recent estimate of the average (mean) male lifespan is nineteen years; J1 was estimated to be fifty-nine years old at the time of his death in 2010.

Females:

-

The estimated average (mean) female lifespan of a SRKW is 35 years

-

Females attain sexual maturity in their early teens; among the Southern Resident orcas, J41 is the youngest known mother (K14 gave birth at eleven, too, but the calf did not survive).

Reproduction

-

Orca mating and calving take place year-round

-

Pregnancies last 18 months, one of the longest gestations of any mammal

-

Newborn calves suckle for short periods dozens of times a day; their mother’s milk is extremely rich, possibly containing 40-60% fat

-

Calves (Baby Orcas) may start experimenting with solid food at a young age but likely do not fully wean until around the age of three

-

Southern Resident orcas have unusually low reproductive output, lower than Northern Resident orcas

-

Approximately 69% of Southern Resident pregnancies result in spontaneous abortion (based on work done using hormones derived from fecal samples); spontaneous abortions correlate with hormonal evidence of nutritional stress

-

Calf mortality is high: a pregnancy has about a one in five chance of resulting in a calf that survives for more than a year; of the orcas assigned an alpha-numeric designation by CWR since 1976, about one in six died before their first birthday

-

The average SRKW female orca birthing rate is currently one viable calf per female every nine or ten years

-

Low reproductive output points toward reduced prey availability and toxins as the main threats to successful reproduction; there is evidence that these two threats interact: toxins become more of a danger when salmon abundance is low and a whale’s body condition is poor

-

Toxins/persistent organic pollutants, like PCBs, are passed from the mother to the calf during gestation and nursing, which could cause pregnancies to fail and young calves to die

-

Controlling for age, SRKW females are more likely to reproduce in years following high Chinook salmon abundance; the survival of calves (and all Southern Residents) correlates with Chinook abundance

-

Females are reproductive until about age 40, then experience menopause

-

Postreproductive females gain indirect fitness benefits by helping family members—remarkably increasing their number of surviving grand offspring.

CWR BLOGS:

Killer whale reproduction

by CWR Research Director Dr. Michael Weiss.

New evidence of menopause in Bigg’s Transient killer whales by Mia Lybkaer Kronborg Nielsen.

LIFESPAN & REPRODUCTION

BABY ORCA(S)

A baby orca surfaces higher out of the water to ensure it gets a “safe breath” of fresh air.

Newborn:

-

Born tail first with a collapsed dorsal fin

-

Six to eight feet long, weighing approximately 400 lbs

-

Fetal folds are present at birth; it takes three to four weeks for a calf to fill out and fetal folds to disappear

-

Orange coloration on underside and eyepatch

-

Typically nurse until sometime in their third year, per stable isotope measures.

Newborn, L125, swimming alongside its mother, L86, on February 17, 2021 (Encounter #8). Note the orangish coloration of her underside and eyepatch.

K39 shows her shedding skin when Spyhopping.

First Six Months:

-

Stay very close to its mother

-

Milk-only diet; usually nurse into its third year; but will begin to eat some solid food around age one

-

Surface higher out of the water than juvenile or adult orca to get a “safe breath” of fresh air

-

Orange coloration on underside and eyepatch

-

Skin shedding occurs

-

Gains strength, size, and weight.

Six Months to One Year:

-

Begins eating solid food (i.e., salmon), although may continue to nurse into its third year

-

Begins to show increased independence

-

Shows lots of exuberant and playful behavior

-

Gradually loses orange coloration

-

Will remain “the baby” until its mother gives birth again (interbirth intervals are highly variable; SRKW, six years).

Calf mortality is high, with one in five dying during their first year of life.

Is it a Girl or Boy?

In 2011, K27’s new calf, K44, was photographed on its side, clearly displaying its sex: It’s a boy! Note the elongated white pattern stretched toward his tail and his orangish-colored underside.

Variations in genital area pigmentation distinguish female and male orcas.

An orca’s sex is determined by the different pigment pattern on the whale’s underside. When a whale breaches or rolls over, the belly is often exposed, giving Center for Whale Research field staff a chance to determine the sex. Male killer whales have an elongated white pattern around their genital slit stretching toward the tail, while a female’s white pattern is more rounded with visible mammary slits (see illustration).

Fortunately, mothers tend to roll their calves around on the water surface, giving researchers a chance to see the calf’s belly and, hopefully, get a photograph. Determining a calf’s sex is vital in gaining information about the demographics and breeding health of the population. During CWR’s five-decade-long ORCA SURVEY, 142 Southern Residents have been born and given an alpha-numeric designation.

VIDEO: “Departed Snug Harbor in Chimo to encounter and check on the status of the new baby, J56. As luck would have it, the first photo that he [Ken] took was of J56 with mom (J31) several miles offshore of False Bay.” September 30, 2019 (Encounter #80).

PHOTOGRAPH: J56 is a girl! Watch and listen to CWR’s Ken Balcomb’s comments in the above video.

It’s a Girl!

This illustration appears in Killer Whales Second Edition by John K.B. Ford, Graeme M. Ellis, and Kenneth C Balcomb, UBC Press © 2000. Used with permission.

Southern Resident orca, L87, during a breach in Haro Strait on September 11, 2021 (Encounter #70). Note its cylindrical shape but tapering at both ends.

ABOVE: Young J57 about to bellyflop near the San Juan Island shoreline on September 30, 2021 (Encounter #80); BELOW: J27 tail slapping on September 5, 2021 (Encounter #63).

Size & Weight:

Females:

-

Females develop to an average of 18-22 feet (6-7 meters) and a weight of 8,000–11,000 lb (3,500-5,000 kg)

-

The largest female measured 28 feet (8.5 meters) and weighed 15,000 lb (6,800 kg).

Males:

-

Larger than females: usually grow to 20-26 feet (6-8 meters) and weight of 12,000 lb (5,400 kg), or more

-

Adult males are distinguishable (sexually dimorphic) by the increased size of their dorsal fin at sexual maturity

-

The largest male on record measured 32 feet (9.8 meters) and weighed over 20,000 lb (9,000 kg).

Calves:

-

Weigh about 400 lb at birth (180 kg) and are 7-8 feet long (2-3 meters).

APPEARANCE & MORPHOLOGY

Unique markings and dorsal fin shape allow Center for Whale Research field staff to identify individual orcas.

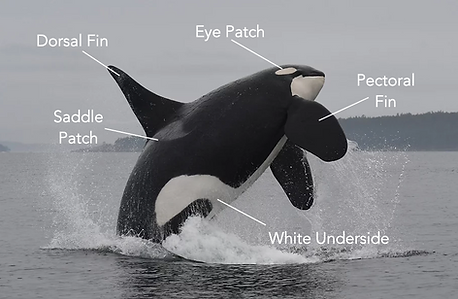

Physical Features:

Body Shape & Coloration:

-

Cylindrical shape, tapering at head and flukes

-

Sharply contrasted black and white “tuxedo” coloring; black head, rostrum, back, sides, pectoral fins, and flukes (topside), primarily white throat and underside, including genitals and the majority of the ventral (bottom) side of its flukes

-

Countershaded: When seen from above, their black skin blends with the dark ocean water; their white skin marries with the light at the ocean surface when viewed from below.

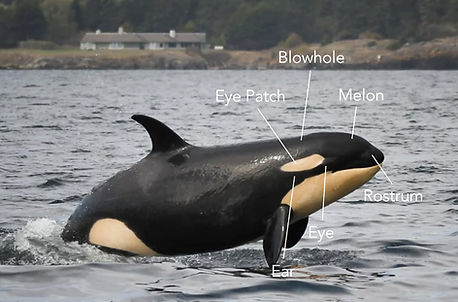

Head:

-

Conical shaped with a small rostrum

-

Single blowhole used for breathing, located on the top of its head between its eyes; a muscular flap covers the blowhole (contracted open to breathe, relaxed and water-tight when closed)

-

Eyes are on the side of its head, just below and in front of its white eye patch, and behind and above the corner of its mouth; orcas have outstanding eyesight (above and below the ocean surface)

-

Small ears with no external flap and posterior to the eye; orcas have a highly-developed sense of hearing and use sophisticated echolocation for hunting prey

-

Mouth contains 10-13 conical teeth on each upper and lower jaw (40-56 teeth total); upper and lower teeth interlock when the mouth is closed; teeth don’t chew food but tear into chunks (or eat the food whole).

Pectoral Fins:

-

Two large, roundish forelimbs are used for steering and stopping, working with the flukes; each contains five digits like humans’ fingers.

Saddle Patches & Dorsal Fin:

-

Grayish-white saddle patch on each side and behind its unique center-back dorsal fin; saddle patch varies from individual to individual in shape, size, color, and scarring

-

Dorsal fin is falcate (curved back) in females and immature males and is straight and up to about six feet tall in males (largest of all marine mammals); males’ dorsal fin reaches its full height between the ages of 15-25 years.

Tail Flukes:

-

Each half of the tail is a fluke; a fluke contains no bone or cartilage, just dense, fibrous connective tissue; muscles in the caudal peduncle (where the tail meets the body) and back move the flukes up and down

-

Males can have tail flukes measuring nine feet across (2.75 meters); flukes curl on the ends.

Brain:

-

An orcas brain can weigh up to 15 pounds.

Blubber:

-

A 3“-4” layer of insulating blubber persists beneath an orca’s skin; stored fat provides energy when prey is scarce.

Breathing:

-

Orcas are conscious breathers

-

Pulse is approximately 60 BPM at the surface and 30 BPM when submerged.

Orca Behaviors

The whales execute many different physical maneuvers and behaviors.

Orca researchers and observers see the whales execute many physical maneuvers and behaviors. See Orca BEHAVIORS for a complete list: The physical action’s name, what happens, and in some instances, an explanation of why.

Some commonly known Instantaneous Behaviors: Breach, Cartwheel, Fluke Wave, Pectoral Slap, Spyhop, and Tail Lob.

Some commonly known Prolonged Behaviors: Feeding, Logging, Milling, Porpoising, Superpod, and Tight.

J45 Spyhop on February 16, 2024 (2024 OS Encounter #16). Photograph by CWR’s Katie Jones.

Sleep

Unlike humans, orcas are voluntary breathers, meaning they have to remember to breathe, meaning that they can’t sleep the same way we do, or they will drown. Studies of bottlenose dolphins and Beluga whales—physiologically similar to killer whales—show that they sleep by shutting down one hemisphere of their brain at a time (USWS/unihemispheric slow wave sleep). It is thought that killer whales “sleep” similarly, breathing while maintaining awareness of their environment, including other pod members.

Orcas sleep for brief stretches day and night, sometimes for as long as eight hours. CWR field staff have often observed this resting behavior: the whales align abreast in a tight group at the water surface and move very slowly forward.

Swimming

Orcas can swim at speeds up to 28 knots (32/mph/50 km/h), but only briefly (1 knot = 1.15 mph = 1.85 km/h)

-

Travel Fast: speed of more than five knots

-

Travel Medium: speed of three to five knots

-

Travel Slow: speed of one to two knots

Southern Resident Orca SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Four levels of social structure have been identified among Southern Resident killer whales.

K Pod composition in 2023.

The Southern Resident orca community (SRKW) is a single clan (J clan) and a single community. Three pods—J, K, and L—constitute the SRKWs. These pods share a common ancestry. The pods socialize and feed together.

Recent scientific research revealed that grandmothers play a critical role in matrilines, pods, clans, and communities. The matriarchs teach the other orcas how and where to fish, and they share the salmon they catch with younger whales in their pod.

Another study found that individuals within groups of associating whales had strong social preferences for particular individuals (“friendships”). The orcas preferred to interact with whales of the same sex and similar age, sometimes with whales outside their family unit. Younger whales and females tend to be the most socially active. The interaction between specific individuals involved physical contact. Findings also showed that orcas are less socially connected as they age.

CWR BLOGS:

Aerial drone view of J47 catching a fish and sharing it with his younger brother J57 (2023 UAV Encounter #15).

Matriline

-

Basic and most important social unit

-

Composed of a female, her sons and daughters, and the offspring of her daughters

-

Strong social bonds

-

Individuals seldom separate from the group for more than a few hours at a time

-

As many as 17 members in a single matriline, five or six members are more usual.

Pod

-

Groups of related matrilines are known as pods

-

Matrilines within pods share a common maternal ancestor from the recent past

-

Most pods consist of one to four matrilines.

Clan

-

Groups of pods that share similar vocal dialects and a common but older maternal heritage.

Community

-

Pods and clans that regularly associate with one another are known as communities

-

Communities are based solely on association patterns rather than maternal relatedness or vocal similarity

-

Four Resident communities are recognized in the Northeastern Pacific: two in Alaskan waters and two in British Columbia and the lower United States waters.

Source: National Marine Fisheries Services 2008

RANGE & COMMUNICATION

Orcas go where the food is and use echolocation (sonar) to find it.

Unlike other whales that follow predictable seasonal migration patterns, orcas tend to go wherever their food source is, making their movement patterns much less predictable.

Residents’ RANGE:

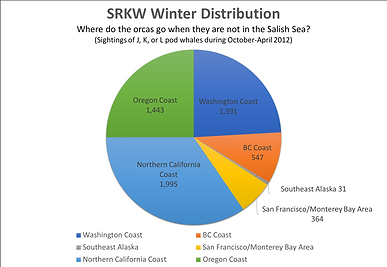

Salmon migrations seasonally influence the distributions of the Resident orcas.

Southern Residents

-

Spring/Summer/Fall Range: Salish Sea and offshore of the Washington and Vancouver Island coasts

-

Winter Range: Research revealed that SRKWs swim up the British Columbia coast as far north as Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands) and south to California’s San Francisco Bay Area; they prey primarily on Chinook salmon but consume some other salmon varieties and fish species.

Northern Residents

-

Spring/Summer/Fall Range: Waters around the north end of British Columbia’s Vancouver Island and in protected inlets along the province’s central and north coast; have been observed as far south as the Washington State coastline

-

Winter Range: As far north as southeast Alaska.

Bigg’s (Transient) RANGE:

-

Bigg’s (Transients) move about in response to the location of their marine mammal prey, such as seals and sea lions; in recent years, they’ve spent more time in Washington State and British Columbia’s inland waters but travel as far as southeast Alaska to California.

Offshore RANGE:

-

Their observed range stretches between the Eastern Aleutian Islands and Southern California.

Click chart to enlarge

Copyright © 2020 Center for Whale Research.

Derivative use requires written approval.

Salmon migrations seasonally influence the distributions of the Resident orcas.

COMMUNICATION

Is a Resident orcas world filled with quiet?

SOUNDS MADE BY

Southern & Northern Resident orcas

No, it’s not. While Residents are mostly quiet at the ocean surface (except for their surfacing “blows” and when they generate loud sounds from slapping or splashing the water surface), they are not so quiet when underwater.

It’s difficult for the orcas to see each other and where they are heading because daytime underwater visibility is typically not more than fifty meters; it’s minimal at night. But the whales must still communicate with one another, navigate their travel route, and hunt for food. Making noise is how they achieve these things. Sound travels very efficiently below the ocean surface and doesn’t discern day and night.

Resident orcas use echolocation clicks to navigate and locate prey and various pulsed call types and tonal whistles to communicate (calls seem more common than whistles). Researchers have identified at least twenty-five Southern Residents—J, K, and L pod—call types. Although not all SRKWs use all calls, they seem to understand the entire language. Researchers have given each call type a letter and number designation (e.g., S1).

Blows

-

The sound is heard when orcas surface (air exchange: exhalation and inhalation); and heard and seen by orca watchers.

Echolocation

-

Used underwater for navigation and hunting for prey; referred to as Click Trains (listen for snaps, clicks, and pops): “Clicks are brief pulses of ultrasonic sound. The reflected echoes act as a biological ‘sonar,’ giving the whale an exquisite perception of the distance and texture of everything within acoustic range (hundreds of feet to hundreds of yards).”

SRKW vocalizations were recorded by CWR staff using hydrophones. Not for use without permission.

Whistles & Calls

-

Used for social communication (listen for different sounds, indicating unique call types): “Whistles and calls are distinctive and can be heard for miles. Each pod has a unique and recognizable vocabulary called a dialect that is stable over time. Dialects are probably an important means of maintaining group identity and cohesiveness while distinguishing pod affiliations.”

SOUNDS MADE BY Bigg’s Transient and Offshore orcas

-

Bigg’s (Transient) killer whales do not share the same basic dialect as Residents

-

Offshore orcas appear to have their own dialects.

HOW ORCAS HEAR

“The whale receives sounds through the lower jaw, where they are picked up by the fat body in the hollow jawbone and carried to the middle and inner ears. Sounds are produced in the nasal sinuses of the forehead and focused by the fatty acoustic lens of the melon. The received sound is focused by the fat bodies in the lower jaw to the Bulla, which is a resonating structure linked to the malleus, incus and stapes and thence to the inner ear, as in land mammals. Whales took an air adapted ear and modified the pathway to work underwater, while retaining the delicate internal ear anatomy—a cochlea.”

Quoted material and illustrations from KILLER WHALES Magnificent Creatures of the Salish Sea by Ken Balcomb and Rick Chandler, Bainbridge Island Historical Museum and the Centre for Whale Research © 2016. Used with permission.

STATUS & THREATS

A changing and unhealthy ocean environment and human behavior are having a profound impact on all orca ecotypes.

Southern Residents (of the Salish Sea):

Protected Status:

-

ENDANGERED in Canada (2001) and United States (2005)

Primary Threats:

-

Lack of Food - Reduced quantity and quality of their preferred prey, primarily Chinook salmon, is due to overfishing by humans, barriers to spawning (e.g., obsolete hydroelectric dams), habitat contamination, and poor ocean survival, resulting in lower reproductivity and higher mortality rates; fewer fish requires the whales to spread out and travel greater distances to feed

-

Environmental Contaminants - High levels of pollutants from commercial, industrial, and household waste disposal and runoff (e.g., pesticides, chemicals from household products, industrial coolants, etc.) enter the Pacific Ocean and advance up the food chain, eventually accumulating in the orcas’ blubber; these toxic chemicals affect harm on the whales and other marine mammals (i.e., immune system repression and reproductive system dysfunction); bioaccumulation of contaminants like PCBs, flame retardants, and motor oil lubricants, are particularly harmful to killer whales; an oil spill in the Salish Sea would be catastrophic for the SRKWs

-

Noise and Vessel Disturbance - Military exercises and vessel traffic disturbance can be deadly for orcas (boat strikes have killed whales in the past); military sonar and weapons testing kills orcas; vessel noise can interfere with the orcas’ echolocation foraging abilities and communications.

Northern Residents (of the Salish Sea):

Protected Status:

-

THREATENED in Canada (2001)

Primary Threats:

-

The NRKWs face the same threats as the SRKWs

-

NRKWs may be more at risk from seismic surveys and oil and gas spills along British Columbia’s north coast

-

Disease associated with ocean-pen fish farming.

Severely-malnourished K21 before his death in 2021, exhibiting peanut head and a collapsed dorsal fin.

Bigg’s (Transient):

Protected Status:

-

THREATENED in Canada (2003)

Primary Threats:

-

Persistent biochemicals in the environment have known harmful effects on marine mammals (e.g., immune system repression and reproductive system dysfunction); bioaccumulation of contaminants like PCBs, flame retardants, and motor oil lubricants, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are particularly harmful to the Bigg’s population

-

Underwater noise and disturbance from vessel traffic

-

Military exercises

-

Potential oil spills.

Offshore:

Protected Status:

-

THREATENED in Canada (2011)

Primary Threats:

-

High environmental levels of persistent biochemicals, such as PCBs and flame retardants that have known harmful effects (e.g., immune system repression and reproductive system dysfunction)

-

Severe and extended acoustic disturbance

-

Potential oil spills.